How the Spanish left-wing party and other movements are using popular television shows to disrupt politics.

By Concepción Cascajosa Virino and Vicente Rodríguez Ortega

In 2014, Podemos emerged as a prominent voice in public debate in Spain after channeling the street protests known as 15-M in an attempt to radically change the state of Spanish politics. This political party was born as a confluence of diverse social groups who shared their rejection of the ruling status quo, finding widespread support among young people, in particular those more likely to use Twitter, Facebook and Instagram; hard-fought battlegrounds in today’s politics, indeed.

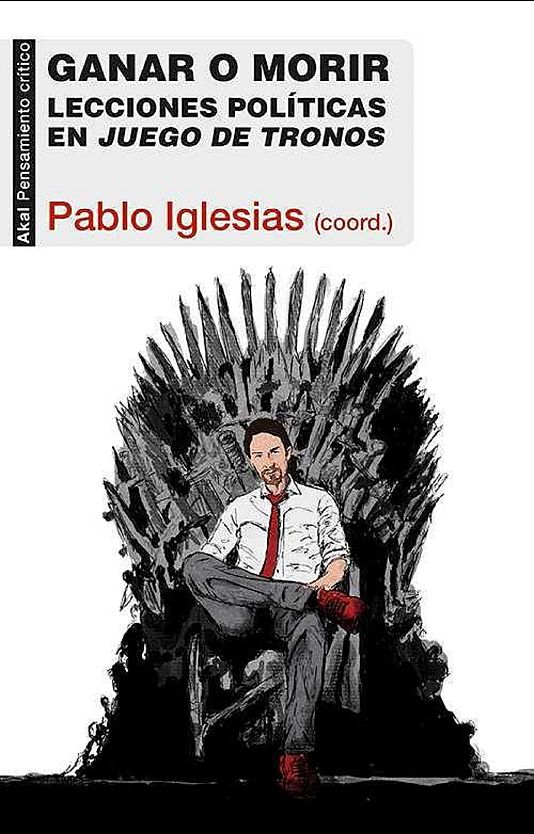

Most importantly, the connection between contemporary television fiction and politics was crystal clear from the very beginning. In fact, in 2014 Podemos’ leader, Pablo Iglesias, had just edited Winning or Dying: Political Lessons in Game of Thrones, a book in which university professors and cultural commentators discussed the concept of power and social change in relation to the popular HBO series. Since then, Podemos has continuously utilized Game of Thrones as a communication tool with its followers. Characters such as Jon Snow, Tyrion Lannister, and particularly, Daenerys Targaryen—outsiders in a violent and corruption-driven universe such as Westeros—have turned into strategic assets for the media-savvy, socially networked Podemos. This fact speaks about the centrality of popular culture, generally, and fiction television, more specifically, in the contemporary social arena. What is more, it also points to the necessary interconnection of television with other digital media. The link between the global hit Game of Thrones and Podemos is the tip of the iceberg. More and more, in the present-day public sphere, television is both a political frontline and a tool to codify our social and cultural behaviors.

Podemos is not the only case in which Spanish politics has been presented through the lenses of different television series. The Twitter account of Izquierda Unida, a coalition that includes the Communist Party, established, at different times, a dialogue with the official account of the time-travel drama El Ministerio del Tiempo (now on Netflix as The Department of Time). In a scene of its second season, the show depicts one of the main characters confronting the police while trying to stop an eviction, a tragically common reality after the economic crisis ravaged Spanish society in the early years of this decade. The smartest community managers of Izquierda Unida’s account (known as “The Cave”), tried to appeal to the series’ fan base, which was both rabid and active on social media.

For its part, during the period of political paralysis between the national elections of December 2015 and June 2016, the so-called “Operation Borgen” began to circulate among the Spanish political class, a reference to the Danish series that had to do with the possibility of forming a coalition government led by a minority centrist party (here, the center-right party Ciudadanos, led by the young Catalan politician Albert Rivera). More recently, when Rivera appeared on the cover of the Spanish version of Esquire magazine, the headline was a quote about his television fiction preferences: "I used to watch Borgen, now I enjoy Designated Survivor". Rivera was here discussing the American television series in which Kiefer Sutherland plays an unknown Secretary of Housing who must assume the post of President of the United States after a devastating terrorist attack.

Elswhere, a particularly interesting case is that of the Icelandic comedian Jón Gnarr. In 2009 he formed The Best Party as a satirical action against the political class after the collapse of the country's banking system. However, the popularity of the party soon became apparent. In the elections for the Reykjavík City Council in 2010, The Best Party won the most votes and Gnarr announced that he would not initiate talks to form a coalition with any leader who had not watched the five seasons of the critically-acclaimed American drama The Wire. After four years as mayor of Reykjavík, Gnarr returned to his day job as a comedian, but in 2016 wrote and starred in a series about his political adventures, Borgarstjórinn (The Mayor).

But, undoubtedly, the best-known case of a television personality reaching the top of political power is celebrity-tycoon-turned-president Donald J. Trump. While still only an entrepreneur, Trump became famous for his regular cameos in movies and television series, including appearances in the comedies The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air, Spin City and Sex and the City. Between 2004 and 2015 he starred in his own reality show, The Apprentice, where his phrase "You're fired!" became infamous. The Apprentice strengthened Trump's popularity and allowed him to garner the status of a dealmaker and problem-solver, an asset that would turn critical, later on, to connect with voters. While in the White House, as Michael Wolff discusses in his book Fire and Fury, Trump has been an avid consumer of television, especially talk shows and political programs, about which he comments on Twitter and from which he draws collaborators. In some cases, Trump, whose use of Twitter is so intense as to receive the nickname of "Tweeter-in-Chief," has constantly discussed television series to appeal to his electorate. The best-known example was his public congratulations to Roseanne Barr for the premiere of the reboot of the sit-com Roseanne, which drew 18.4 million viewers.

To sum up, political forces such as Podemos are disrupting the status quo of traditional parties using ideologically-charged symbols from television and other popular culture to connect with potential voters. This tactic sets up multimedia narratives as the lens through which the movement’s politics and its place in society are perceived. This kind of “participatory culture” empowers internet-savvy, socially networked supporters to become at once both fans and political activists. Podemos and Game of Thrones is perhaps the most obvious and well-known case, especially in the Spanish context, but it is far from being unique. This practice is common currency in today’s cultural and social fabric.

In today’s digital mediascape, Podemos’s astute use of Game of Thrones has sparked a myriad of discourses that digital users have weaved through their own positions and political agendas. Initially, this allowed Podemos to mobilize online political activists. Subsequently, it has become a tool for the party’s strategy to engage with its supporters—via the deployment of the users’ free labor itself— by making explicit connections with Daenerys Targaryen’s quest to seize power and other compassionate characters such as Jon Snow. It is impossible to firmly establish the role of television in Podemos’ electoral results but we should certainly acknowledge its key importance in its communication approach. At the very least, we can affirm that the use of Game of Thrones has helped to increase Podemos’ media exposure and its steadfast popularization. Ultimately, the Podemos-Game of Thrones association points to a new type of fan engagement, where the active consumption/production of media artifacts and their dissemination through social networks has become a central area of political activism.

Concepción Cascajosa Virino is a senior lecturer and Vicente Rodríguez Ortega is a junior lecturer, both at Carlos III University of Madrid where they are members of the research group Television and Cinema: Memory, Representation and Industry (TECMERIN).