Mark Rowe reports on the failure to agree on an international treaty to limit plastic pollution and what our best hopes are for the future

More than 3,300 politicians, government officials, scientists and lobbyists – including conservationists and chemical industry figures – from more than 170 countries and 450 organisations participated in the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee on Plastic Pollution. Its fifth, and supposedly final, round was held in Busan, South Korea, in December to sign off on the first legally binding international treaty to tackle a problem most assumed was commonly accepted as needing urgent action. It collapsed with no agreement and much rancour.

Enjoying this article? Check out our related reads:

While 100 countries agreed on placing a cap on plastic production, several nations, including fossil fuel giants, opposed the measure.The link to fossil fuels answers a question that must puzzle many casual observers: why is a reduction in plastic production even remotely contentious?

Louise Reddy, from Surfers Against Sewage (SAS), points out: ‘The UK public and the UK government agree we need to get a handle on the plastic crisis, but there are other interests at stake. With fossil fuels being targeted for reductions, oil and gas companies have their eyes on plastic as a new way to grow their businesses. At the treaty talks, oil and gas lobbyists outnumbered the scientific representatives three to one.’

A global problem

There’s no denying the scale of the problem. The UN calculates that since 1950, more than eight billion tonnes of plastic have been produced globally, but less than ten per cent has ever been recycled. The UK government says 100,000 marine mammals and turtles and one million seabirds are killed by marine plastic pollution every year.

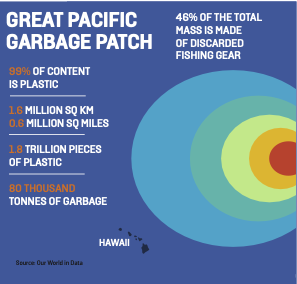

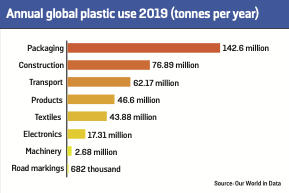

An OECD report, Global Plastic Outlook 2022, found that in 2019 alone, 6.1 million tonnes of plastic waste leaked into rivers, lakes and oceans. In 2023, scientists found a plastic bag 10,975 metres down in the Mariana Trench, the world’s deepest ocean point. The North Pacific Ocean Garbage Patch (between Hawaii and California) now spans 1.6 million square kilometres, but our oceans are now home to five such patches, with vast vortexes of marine trash also coalescing in the North Atlantic, South Atlantic, Indian Ocean and South Pacific.

Microplastics are perhaps the most intractable elements of the plastic problem. Defined as smaller than five millimetres in size, an incomprehensible number – perhaps 358 trillion microplastic particles – are floating on the surface of our oceans, according to a 2023 study led by the University of Auckland, with ‘untold trillions more’ in deeper reaches. Sources include tyre dust, synthetic fibres from fast-fashion items (a washing cycle can release up to 700,000 synthetic fibres from common fabrics such as polyester and acrylic), fishing nets, ropes, plastic sheets, beads from cosmetics and fragments of larger plastic items that have broken down over time.

These tiny particles are easily mistaken as food by marine life, thereby disrupting ocean ecosystems by altering nutrient cycles and harming microbial communities that sustain life. A 2022 study by the UK’s International Marine Climate Change Centre found that microplastics are forming a new geological layer in the Earth’s seabed sediments. Corals, mangroves and seagrass beds are also smothered by plastic waste, preventing them from receiving oxygen and light, while the Netherlands-based The Ocean Clean Up has warned this potentially interrupts the grazing behaviour of zooplankton.

The message from scientists and campaigners is that plastic pollution requires the same urgency as climate change. ‘Air, water, soil and every living organism is now infected with plastic,’ says Sian Sutherland, co-founder of A Plastic Planet & Plastic Health Council. The SAS, which has long been campaigning about plastic pollution, says one in three fish caught for human consumption contains plastic. ‘Plastics break down into smaller and smaller pieces; these tiny plastics enter the ocean food chain and have been found inside humans,’ says Reddy, senior policy officer at SAS. ‘We must stop them at source from wreaking even more havoc on the ocean.’

Microplastics are being stripped from seawater and blown inland, according to Lauren Biermann, a marine remote-sensing scientist at Plymouth University. ‘A rapidly growing body of medical evidence demonstrates that inhaled microplastics and nanoplastics can persist in the body, with demonstrable negative impacts on the viability or health of cells, tissue, animals and people,’ she says.

Plastic pollution is intertwined with climate change: it’s produced from fossil fuels and is estimated to be responsible for five per cent of global emissions (around 90 per cent of emissions from plastics come from production; 2.5 tonnes of carbon dioxide are generated by one tonne of plastic). ‘Climate change shares the same roots with plastics and, unfortunately, many of the same challenges,’ says Biermann.

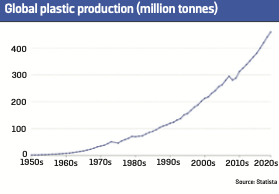

Yet plastics production is expected to be one of the leading drivers of oil demand growth over the coming years. The UN reports that annual global production of plastics and plastic waste doubled in 2019 compared to 2000 and is forecast to triple by 2060. ‘It’s a sector flagged for rapid growth by the fossil fuel industry, including petrochemical and packaging companies,’ says Biermann.

According to Carbon Brief, without any agreement to cut plastic production, emissions from plastics could consume half of the remaining carbon budget for limiting warming to 1.5C above pre-industrial levels.

Reduction at source

‘The ubiquity of plastic in the environment means that it is nearly impossible to rid the world of all plastic pollution,’ says Sutherland. ‘While there is value in have, we must not rely on downstream solutions that will never be able to keep up with the rate of production.’ Reducing plastic production at source is the surefire way of ensuring this mountain of toxic waste does not climb higher’, says Sutherland.

The scale of ocean plastic pollution was highlighted by the work of marine scientists such as Biermann, who, in 2020, was the lead author of the first successful study to use satellites to detect marine plastic pollution. She said she hoped the report would be a stepping stone for further deployment of satellites and drones to meaningfully tackle the marine plastics problem.

An earth champion

In 2023, the UN Environment Programme declared Josefina Belmonte, mayor of Quezon City in the Philippines, a Champion of the Earth for her efforts to tackle the tide of plastic blighting her city’s urban and riverine landscapes. Her initiatives included bans on single-use plastics, a trade-in programme for plastic pollution and refill stations for everyday essentials.

A key target was the millions of single-use plastic sachets thrown away every day in the Philippines. Although sachets allow households more affordable access to essentials for cooking, hygiene and sanitation, they can’t be recycled effectively.

In 2021, Belmonte passed regulations enabling residents to trade in their recyclables and single-use plastic products for environmental points that can be used to buy food and pay electricity bills under a Trash to Cashback scheme. In 2023, she set up an initiative to install refill stations for essentials, such as washing-up liquid and liquid detergent, in convenience stores across the city.

The wide dispersal of plastics in the open ocean makes the search for what Biermann describes as the ‘gold standard’ of detection and clean-up difficult. Coastal waters, where detection is much easier, have greater potential, as drones and very-high-resolution instruments can guide targeted beach cleans, although Biermann points out that oceanographic features tend to be ephemeral. ‘What was seen yesterday may be miles away by tomorrow,’ she says.

Reddy believes the focus should be on turning off the plastic tap, rather than sieving the oceans. ‘Beach cleans and many other clean-ups have a crucial part to play,

but it is the stopping more getting in that is even more important,’ she says.

‘While the huge volume of plastic that has already been tossed into the ocean is causing huge problems, it is critical that we don’t get caught up in picking our way out of this problem. Cleaning up a mess that already exists will mean nothing if we are pouring more into the sea at an even faster rate.’

The line marking where responsibility lies – with the producer or the consumer (that is to say, us) – can be fuzzy. In the case of plastic, Reddy argues consumers have had little choice. ‘Like all environmental issues, plastic is completely interlinked with a consumerist society, focused on production,’ she says. ‘We know that people want to change, but we also know that with such a strong lobby from industry, it is the public who will have to push for better. That is why we are encouraging communities to turn their back on single-use plastic and demand better from business and the government.’

Consumers should not be made to feel guilty, argues Sutherland. ‘The rise of plastic and the rise of hyper-consumption have run in perfect unison; there is symbiosis in the existence of each,’ she says. ‘The consumer is not to blame for the plastic crisis. Plastic is cheap, and it is used in nearly every product we buy. This is not a result of consumer demand; it is a result of the normalisation of a material in our daily lives that harms our environment and health. While there is no risk of liability or financial loss, industries will stick with using plastic as a primary material.’

Recycling, the obvious option, is tricky to unpick. The word ‘plastic’ describes a wide range of human-made polymers, and the biggest barrier to plastic recycling is often separation: when different polymers are mixed, the resulting material doesn’t usually have useful properties. Even two plastic items, a drinks bottle and cookie cutter, for example, may have different melting temperatures that produce an unusable sludge when combined.

A 2023 UN report, From Pollution to Solution, poured cold water on the chances of recycling our way out of the plastic pollution crisis.

The authors warned against damaging alternatives to single-use and other plastic products, such as bio-based or biodegradable plastics, ‘which currently pose a chemical threat similar to conventional plastics’. Instead, the authors concluded that ‘ultimately, a shift to circular approaches is necessary, including sustainable consumption and production practices, accelerated development and adoption of alternatives.’

‘Even if all plastic were to go into a recycling system, the material can only be “recycled” two or three times before its quality substantially deteriorates,’ says Sutherland.

When it comes to non-synthetic plastic materials that can provide the same service, the picture is changing quickly. Biopol, the first biodegradable plastic, only emerged in 1990 (for a shampoo bottle) and, like early semi-synthetic plastics, was derived from natural, biological material such as corn starch.

Innovations are returning to this approach. ‘Products made from natural materials that return to the earth after use, working with the planet and not against it, are available and being scaled,’ says Sutherland.

Examples include Natural Fibre Welding, which has created a plastic-free alternative to leather from natural rubber and pigments, and recycles cotton and other fibres into footwear and furniture; ShellWorks, which makes Vivomer, natural polymer granules created by micro- organisms; and RyPax, which produces packaging from recycled corrugated pulp, paper and fast-growing natural fibres such as bamboo, bagasse and reeds.

‘The message to those corporates with their head in the sand is to embrace the opportunity presented by a post-plastic economy and be the first to reap the rewards,’ says Sutherland. ‘Now is the time for a revolution in how we design what we buy, use and work with every day. Systems of refill, which used to be the norm, are also coming back bigger and better than ever, helping to shift us back to a circular mindset that doesn’t view every item as something to be disregarded with immediacy.’

UNEP is determined that the INC talks will resume this year. Measures on the agenda include setting controls on virgin plastic production, agreeing on restrictions for the most hazardous and problematic polymers, establishing clear criteria for eco-design and product standards, and agreed methodologies for monitoring and reporting on plastic and plastic pollution. Campaigners such as SAS are also calling for ‘stable and predictable financing’ to ensure developing countries and economies in transition can meet the obligations of the agreement.

‘The breakdown [of the INC talks] was disappointing, but it is by no means the end,’ says Reddy. ‘The Global Plastics Treaty, the first-ever global commitment to end plastic pollution, is so close to being agreed. Now is the time to keep the pressure on to make sure the treaty delivers for people and the planet.’

Sutherland describes an agreement as ‘fundamental’ to a more sustainable industry. ‘This is the first example of countries coming together to address plastic pollution once and for all with a legally binding treaty,’ she says.

The great clean-up

Microparticles could be filtered out by municipal and wastewater systems using processes such as coagulation and flocculation, whereby coagulants neutralise the surface charges of microplastics, and flocculants encourage them to bind together to form larger groups that are easier to capture.

Scientists at Groningen University in the Netherlands are trialling a magnetic fluid made from oil and iron oxide to which microplastics attach themselves; a magnet then removes the solution, leaving behind only water. Feasibility work is examining how to fit the technology onto ships, in effect as a dragnet, so they can extract plastic as they sail the world’s seas.

The Ocean Clean Up is testing a range of clean-up systems that apply barge-like structures equipped with filters that work like flanges in the beaks of waterbirds or whale baleen. These include an interceptor that comprises a standalone floating barrier anchored in a U shape around the mouth of small rivers, and a tender that scoops up rubbish and offloads it into a dumpster onshore. In 2023, the organisation installed a barricade in the Las Vacas River in Guatemala to catch plastic washed downstream during the rainy season.

An interceptor guard has been installed in the harbour at Kingston, Jamaica, to catch plastic in shallow tidal waters. The guard works as a no-return boom, preventing rubbish from being pushed back upstream by wind and waves.

At the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, a long U-shaped barrier, known as System 03, guides plastic into a retention zone at its far end, in effect creating an artificial coastline to concentrate the plastic. The Ocean Clean Up says ten such full-size systems would be sufficient to clean up the garbage patch.

‘Litigation is building momentum. The treaty will undoubtedly bring further scrutiny to the doorstep of industry if implemented in 2025.’

Campaigners and scientists are certainly not Luddites and recognise that plastic has a place in society. ‘Plastic is a brilliant material,’ says Reddy. ‘It keeps us safe, helps us heal and provides a vital service in shaping our homes and lives. That’s why it’s crept its way into every aspect of our lives.’ But, she adds, governments and society need to move from a linear system where individual items are used and thrown away, cut plastic use where it is not needed, and reuse, repair and recycle it wherever possible. ‘Plastic has crept too far. The world is addicted to unnecessary single-use plastic and we need a detox.’

The oil industry will take some budging, warns Sutherland. ‘Plastic is [their] plan B. They are desperately clinging to a business-as-usual model that has caused untold damage,’ she says. ‘They have manufactured a mentality within society that we are able to take, make and waste with no consequences. We have been led to believe that plastic is not a problem if we are a good citizen and sort our rubbish into the right bin; then all will be well – plastic will just be recycled.’

Perhaps the most positive step change is a psychological one, argues Sutherland – what she calls ‘the removal of the veil of a single-use mindset’ that is at the core of seeing the change required with how we, as a society, consume.

‘Plastic is a cheap material with miracle properties, but it is toxic to both humankind and the planet; it has no place in a regenerative economy,’ she says. ‘We need business to wake up, move the money to the materials and systems of the future, and protect the health of their customers rather than the healthy bottom line of the fossil fuel industry.’

Biermann feels efforts to regulate plastic could go either way. ‘I am an eternal optimist, but I am cautious about being too hopeful here,’ she says. ‘Hundreds of countries have been passionate, outspoken, and immovable in their support for a legally binding International Plastic Treaty. It would be tragic if globally united voices calling for a cleaner and safer planet become drowned out by lobbying from industry associations, along with chemical, fossil fuel and oil companies.’